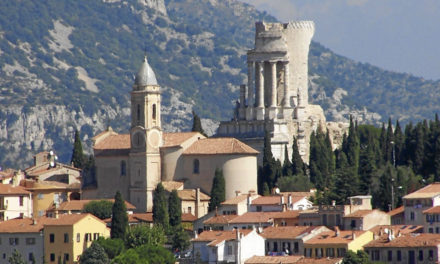

Bourg-en-Bresse, capital of the Bresse and, since the Revolution, of the Ain, served throughout much of medieval times as a major outpost of Savoie (or Savoy). Briefly seized by French King François I in the 16th century, the Bresse was returned to the Duke of Savoy in 1559. A huge citadel matching that of the new, safer Savoyard capital of Turin , went up in Bourg to guard against future attacks by the French who came back to lay siege in 1600. The citadel was demolished and from 1612 no sign of it remains. However, some lively historic shopping streets slope down the town’s hillside, the odd remarkable timber-framed house along the way, while the main Gothic church still stands out prominently, in particular thanks to the addition of bright Baroque towers. In the grand grey interior, the wooden stalls are carved with saints, aristocratic faces, jesters, and fighting dogs and dragons, all joyous to behold.

Hotels in Bourg-en-Bresse

History 1

But these delights pale compared with the artistic riches at Brou, an historic suburb a mile east of the centre. The attention focuses on its splendid triple-cloistered abbey much of which has been turned into an art museum. First visit the tour de force of a church, a flamboyant Gothic extravaganza by the Flemish architect Loys Van Boghem, built between 1513 and 1532, signalled by its multicoloured roof tiles in Burgundian style. The abbey’s main benefactor, Marguerite of Austria, a woman of exceptional importance on the 16th-century European royal scene, stamped her mark on the place, depicted with her second husband Philibert de Savoie on the tympanum of the main façade with its intriguing tracery patterns. One of the best connected figures of Renaissance Europe, Marguerite, was born in 1480, daughter of Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian and Mary of Burgundy, to become aunt of both the formidable Emperor Charles V and King François I of France. Dreadfully unlucky with men, as a girl she had been engaged to the future King Charles VIII of France, but still in her youth, was, for political reasons, sent packing in favour of Anne de Bretagne. Then in 1497 she was married to the Infante Juan of Spain, who promptly died within a few months. Philibert le Beau of Savoy scarcely fared better, the irresponsible, fun-loving huntsman lasting a mere three years after their marriage in 1501. Despite the curse, the devout Marguerite remained a determined, exceptionally capable figure. Made regent of Flanders for the future Emperor Charles V in 1507 by her father, for Brou she carried out her mother-in-law Marguerite de Bourbon’s wishes to rebuild the run-down abbey, directing operations from Malines in the Low Countries. Although, thanks to her position and wealth, she was able to pour in vast sums to have this great mortuary of a monastery built as swiftly as possible, she died two years before the church was officially completed.

History 2

Inside the church, the carved stone rood screen at the end of the quite sober nave hints at the splendours to come in the choir. Few more elaborate and dignified lordly tombs have survived in France than those of Marguerite and Philibert, while his mother was accorded a more modest one. The couple are each represented twice in idealised form, above in finery, overseen by classical figures and chubby naked putti, below in death, Marguerite’s body wrapped in a shroud, Philibert’s naked, rivalling that of Michelangelo’s David in staggering beauty – as Philibert’s nickname indicates, he was renowned for his good looks. The tombs designed by Jean de Bruxelles, the highly flattering main figures were executed by the German sculptor Conrad Meit. The couple are depicted again in the splendid stained glass, devoted, somewhat understandably, given Marguerite’s bad luck with marriage partners, to the theme of resurrection, and inspired by engravings by Dürer. The church’s wooden stalls depict biblical scenes with carvings bordering on the neurotic, such is their extraordinary intensity, putti playing under seats depicting the vices.

History 3

Augustinian monks prayed for the lords of the land here up to the Revolution, when the place was only just saved from destruction. Two of the cloistered courtyards contain further Gothic figures in stone, but the more rustic, cobbled third proves the prettiest. The vaulted main rooms and the cells have been converted into the Ain’s main fine arts museum. Medieval religious statues now fill the refectory with life. Amazing 16th-century paintings include a Burgundian triptych of St Jerome and a Flemish Christ flanked by utterly miserable angels, while Marguerite and Philibert crop up again in less idealised fashion, in portraits. Gruesome pieces include two monks flagellating themselves, definitely at the weirder extreme of the religious spectrum, and Gustave Doré’s depictions of Dante’s Inferno. But you can also enjoy some less disturbing Dorés and delightful local landscapes by Chintreuil. Utrillo and Utter also left colourful renditions of Rhône-Alpes scenery. Serene contemporary pieces well suited to the surrounds stand out in the cloisters. Local crafts have their place too, particularly ceramics produced in Meillonnas, a village reputed for its pottery, sat on the wooded ridge of the Revermont that forms the eastern backdrop to Bourg. Emaux Bressans Jeanvoine is the one craftshop in town still making the traditional enamel jewellery encrusted with bright beads that was particularly fashionable in the Belle Epoque. For more on the Bresse, read the Cadogan guide to the Rhône-Alpes. Copyright Philippe Barbour 2011 Copyright Images Region Urbaine de Lyon.